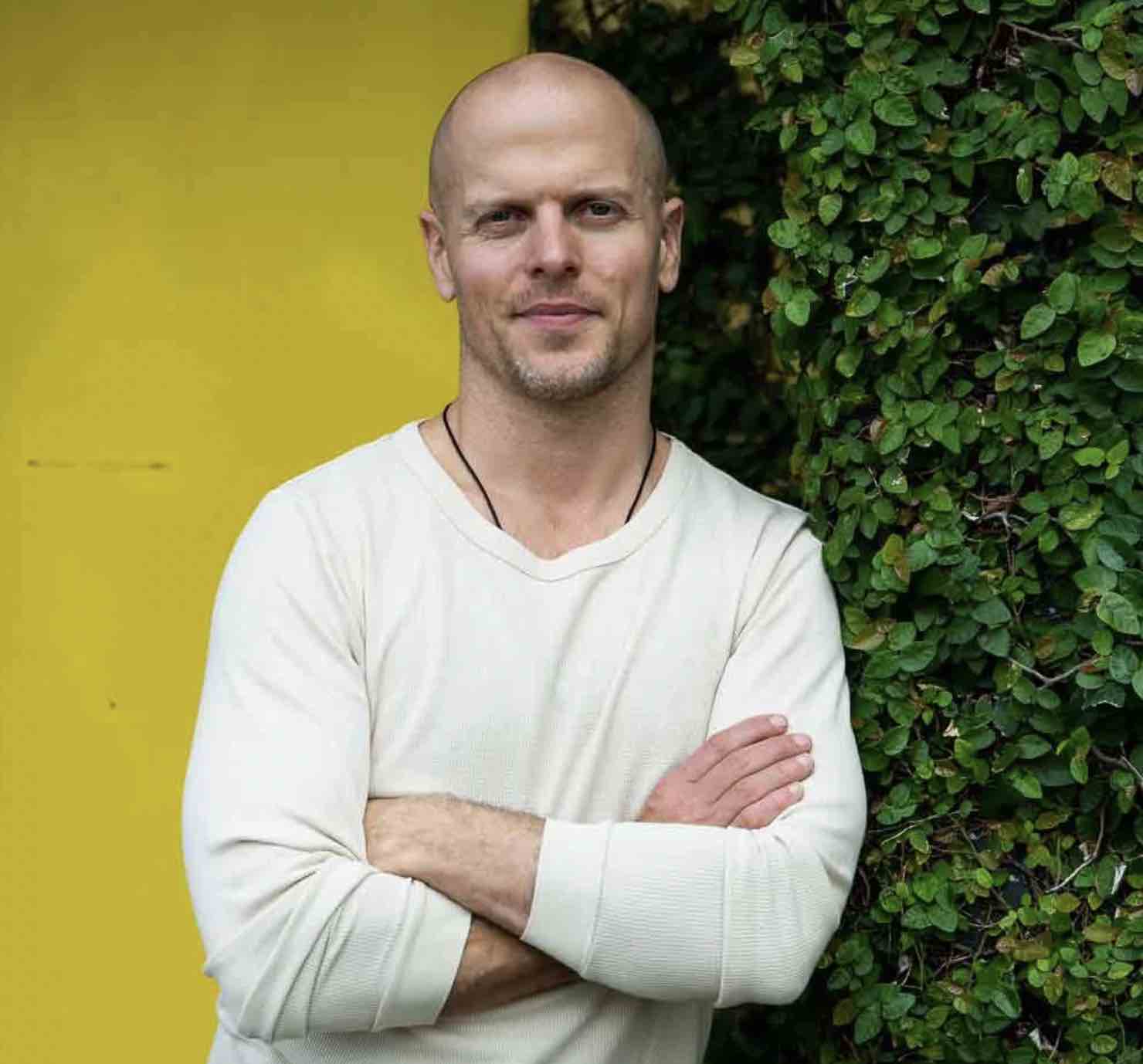

It’s my pleasure to interview Tim Ferriss, an entrepreneur, investor, author, podcaster, and lifestyle guru. If you know the book The 4-Hour Workweek, you know who he is.

Tim speaks six languages, runs a multinational firm from wireless locations worldwide, a national champion in Chinese kickboxing, and has been a popular guest lecturer at Princeton University since 2003.

In this interview, I ask Tim about his views on productivity and 20/80 rules. Tim also gives me some great answers on his thoughts on lifestyle, work life, and outsourcing.

An Interview With Tim Ferriss

Q: Tim, you have done a lot in your life – you are a kickboxing champion, a world record holder in tango, as well as running a multinational firm. What other things have you done in the last few years? Which are the things that you are most proud of?

There are a few fun ones that stand out, like finally training in kendo in Japan, where I killed myself last September and fulfilled a life-long dream, but I’m definitely most “proud” of conquering two fears.

Learning to surf in Florianopolis, Brazil, was a huge win for me because I can only use one lung fully (due to being born prematurely), and I’ve always been deathly afraid of drowning. One good friend and I actually reserved a VIP table at the world-famous night club Confraria there — $60-100 USD per night — so I could finish editing my book over red wine and dancing locals at night. It was incredible, and I owe a lot to my friend, Chris, for keeping me from panicking in the water.

Second, writing this book required me to conquer serious inner demons. I was mildly dyslexic at a young age and still have a lot of trouble with dygraphia: miswriting and mixing up letters. Finishing my senior thesis in college almost killed me, and this book was more than twice the length. I’ll just remember the advice my former professor and Pulitzer prize winner John McPhee gave me when I first sold the book: “When it seems like writing is really, really hard, just remember: writing is really, really hard. I sit in front my my typewriter from 9 to 6 each day, and most of the time, I get nothing done.”

Q: Your book, The 4-Hour Workweek, is extremely successful. Why do you think it is so popular and the idea is widely accepted?

There are a few reasons. First, the topic hit at the right time. Forbes recently reported the new average workweek as 70 hours, and this will only increase. It’s unsustainable, just as I realized in 2004, and people want alternatives to postponing life for 20-30 years for a nebulous “retirement”. The 4-Hour Workweek offers a different menu of options — mini-retirements, outsourcing life, etc. — many of which people haven’t really seen before.

Second, I didn’t follow a top-down, Oprah-as-messiah PR and marketing plan. I’d love to be on Oprah, but seeking that stamp of approval is a gamble for a first-time author.

For those familiar with Glenn Reynolds book “An Army of Davids”, I embraced a few groups of Davids and took an bottom-up approach, embracing thought leaders where possible, to harness the most efficient word-of-mouth network in the history of the world: social media.

I give away plenty of ideas and stir up discussions — and arguments. I just want people to talk, and when you create enough noise, the books move. It hit the NY Times and Wall Street Journal lists based on the first 4 days of sales with no offline PR or advertising, and it’s been in the Amazon top 15 or so for five weeks now. I hoped for this, but I never could have expected it all to come together so well. Plenty of luck involved, I’m sure!

Q: I love preaching about productivity, but you are taking productivity to the next level – wow, the 4 hour work week. I would say it is the holy grail of work-life. What are your tips to achieve this kind of productivity in your life?

Think instead of react. Take frequent breaks and strive to constantly eliminate instead of organize. Create not-to-do lists and cancel, fire, subtract, and eliminate, eliminate, eliminate. If you remove all the static and distraction, priorities become clear, execution becomes a one-item to-do list, and time management isn’t even necessary.

Honestly, this is the holy grail. It took me a long time to figure out that, in a digital world of infinite distraction and minutiae, he who has the least number of programs running in mental RAM wins.

Every time. I’ve interviewed everyone from gold medalists to CEOs who make $100 million a year, and their one common characteristic is the ability to “single-task” without interruption. It’s deceptively hard if you don’t have a solid method.

Q: I am a fan of the 20/80 rules, as you are. I realize it is not a scientific formula, but it gives an air-horn alert on what should we really be focusing on. People ask me how to effectively identify the 20% of work which produce the 80% of the output. What are your key factors to assess this?

Before we analyze, we have to answer the question: what are the metrics that matter?

The metrics that matter are those that measure your progress towards a well-defined goal. Is it $X in profit? Is it a certain income-to-hours ratio? If you can’t measure it, you don’t understand it.

To quote Peter Drucker: “what gets measured gets managed.” Let’s say it’s income-per-hour. I would first apply the 80/20 principle to a few areas: what are the 20% of customers/products/distributors that are producing 80% of the profit?

Then we do the less common; we apply 80/20 to the negative: what are the 20% of activities and people that consume 80% of your time? Fire high-maintenance, low-profit customers; create communication barriers for time-consuming colleagues; train your boss to value performance over presence with clever documentation, create a not-to-do list of your “crutch tasks”, and outsource the rest.

There is another approach for determining the critical few. Limit time. Here’s where we apply the lesser-known Parkinson’s Law, which dictates that a task will swell in perceived difficulty and complexity in direct proportion to the time we allot it.

For example, if you suddenly find out that you have an emergency and need to leave the office at 2pm, what happens? You miraculously get the most important work done three hours early. In other words, we can use the 80/20 principle and Parkinson’s Law hand-in-hand.

We use the 80/20 principle to limits tasks to the important to reduce time. We also use Parkinson’s to reduce time (short deadlines) to limit tasks to the important. Pretty cool — and jaw-droppingly effective — when used together.

Q: You mentioned elimination is the key element in your productivity system. How is it different than optimizing process or system to save time? What type of people should take one or the other approach, or both together?

I think they’re the same thing — in my world. “Optimize” should mean removing the non-essential and minimally important until you’re left with the bare essentials necessary for producing the target result. This is what Arthur Jones, founder of Nautilus, would call the “minimum effective load”. Think 37 Signals and Occam’s Razor.

Unfortunately, this word “optimize” is so overused as to be meaningless, so people usually use it to justify endless addition — of features, customers, options, rules, etc. — that complicates instead of simplifies.

I wanted to be a comic book artist, a penciler, for almost a decade, and I still stick to the philosophy one New Yorker cartoonist taught me ages ago: when in doubt, black it out. Fewer is better and less is more. Perhaps you have an issue, a product, a situation, or a person that is extremely difficult to fix? Consider just eliminating them.

Q: You mentioned about it is all about living the lifestyle with limited income. Do you mean it is all about controlling your input to get the output you really need, and use the spare cycles to do what you really want to do? What are your advice for people to idealize their actual lifestyle?

It’s actually not so much about living with limited income; it’s about determining exactly how much income you need to have your ideal lifestyle, then leveraging time and mobility (geoarbitrage and such) to get there in as short a period as possible, usually a few months.

What would you have and do each day if you had $100 million in the bank and had already retired? This is not BS — this is THE question you have to answer.

If you want to drive a yellow Lamborghini Gallardo, visit Fiji once a year, and ski in the Andes each winter for a month, add it all up and determine the average monthly cost. Add your current essential fixed expenses to this (there are free calculators for doing all of this), and you have what I call your TMI — Target Monthly Income — and TDI — Target Daily Income. The first step to achieving your ideal lifestyle is defining it and calculating the actual cost. It’s always less than you think.

Here are just two personal examples of what’s possible once we reset the rules: for $250 USD, I spent five days on a private Smithsonian tropical research island with three local fishermen, who caught and cooked all of my food and took me on tours of the best hidden dive spots in Panamá; for $150 USD, I chartered a plane in Mendoza wine country in Argentina and flew over the most beautiful vineyards and snow-capped Andes with a private pilot and personal guide.

I’ve done even more outrageous things in places like Tokyo and Oslo. It’s really possible to do these things now, and it has nothing to do with going to third-world countries. There is no reason to wait 30 years.

Q: What advice do you give if one’s idealization on all about luxury which requires a lot of income to support that, and won’t settle for anything less?

I can show you how to drive a Ferrari Enzo and Larry Ellison’s famous McLaren F1 for $300. No joke. That said, once people create time abundance, showing off shiny objects becomes a far second priority to answering the question “what the hell do I do with my time?”

The big existential questions most people face at college graduation, mid-life crisis, and retirement don’t go away with faster cars, bigger homes, and better martinis.

I say go ahead and go nuts for a while with material excess, but if people streamline to the point where income generation only takes 4-10 hours per week, the “what to do” is the real challenge… and reward. I’ve never found an exception.

Q: Do you think this is not suitable to people who are really passionate about their work? I do not mean a workaholic, but someone who is enjoying their work as much as traveling around the world.

Not at all. The title “The 4-Hour Workweek” is easily misinterpreted, but this book isn’t about idleness at all. It’s actually exactly the opposite. I’m always working on something, but that “something” is exciting to me and keeps me up like a kid on Christmas Eve.

The 4HWW is about creating an abundance time and spending it on whatever excites or fulfills you most. Take this book launch, for example. I’ve spent a ton of time on it because I’m having an absolute blast. I did none of the really boring stuff, and my learning curve is insanely steep right now. As soon as that plateaus, I’ll disappear to Croatia for a few months or do something else.

But here’s the other issue: there is such a thing as too much of a good thing. Ask any pastor suffering from “compassion fatigue” or book editor with too many books on her plate.

Even if you love your work, controlling the volume and keeping work and life separate is critical. I think “dream jobs” are a very misleading and dangerous myth.

Q: I have experienced couple outsourcing services and found out I spend a lot of time writing specific instructions for them to complete the work. Do you have examples of task which you have given them to work on? What are your tips to optimize the workflow/process between you and them?

Hire teams that specialize in one or two functions, and use them for repetitive time-consuming tasks.

If you follow just these two guidelines, you avoid training people more than once, you avoid overtaxing them with non-core expertise, and it becomes more of a “set it and forget it” model.

Don’t look for a personal Jack-of-all-trades. Think in terms of departments and teams. If you want a great mix of smooth communication and unreal pricing, find Americans in developing countries. I have virtual American MBAs in places like Croatia and Jamaica who charge $5/hour.

I use one group for web design, another for online research and Excel spreadsheets, and another for researching purchase options and making suggestions (for a Baltic States trip or buying a high-altitude simulation chamber, for example, two recent projects of mine). Prevent expensive miscommunication by asking for a written progress report after three hours on any 10-hour+ task.

The range of tasks is truly mind-boggling. Anything you can do in front of a computer or phone can be outsourced, from white papers for a Fortune 10 conglomerate to your personal life. I outsourced all of my online dating for 4 weeks recently as a joke to win a bet. There were teams around the world competing to set me dates on an online calendar. The result? More than 20 dates in three weeks. It’s amazing what you can do. The options are limitless.

Q: Is outsourcing is the only way to scale? You mentioned productizing expertise on the other interview. What exactly do you mean? Do you have any other ideas to scale your efforts?

Outsourcing is just one option, one small piece. It’s actually entirely optional but too fun for me not to recommend.

How do you scale results without scaling effort? You need external products and processes. Get the expertise out of your head.

For the business owner or manager, that might mean a comprehensive FAQ and step-by-step operational manual for each role in the company, or simply a small set of principles and rules you use for fast decision-making that others can duplicate. The switch is from adrenalin- or leader-driven to process-driven.

For the employee or freelancer, “productization” simply means capturing your expertise in a physical form, whether a piece of software or a book. Only then are you able to totally separate income from time, remove ass-in-seat time as your limiter, and make $10,000 per day as easily as you make $100. Creating a scalable life isn’t as hard or time-consuming as it seems.

Q: Thank you so much for your time, Tim. Oh, and one last question, since you are a reader of lifehack.org, what are your favorite posts since you subscribed?

Man, that is hard. As a Firefox geek, the “15 Coolest Firefox Tricks Ever” got me embarrassingly excited. Ah, the small pleasures!

Thanks for getting in touch! Keep up the rocking site!

Bottom Line

I hope you have learned something new and inspiring from Tim Ferriss. He truly is a guru for life and productivity.

If you want to learn more about the 80/20 rules mentioned in the interview, check out What Is the 80 20 Rule (And How to Boost Productivity With It)