Selling candy bars can teach you a lot about building better habits. Before I tell you why, let’s start at the beginning.

The Science of Candy Bars

In 1952, an economist by the name of Hawkins Stern was working at the Stanford Research Institute in Southern California, where he spent his time analyzing consumer behavior. During that same year, he published a little-known paper titled, The Significance of Impulse Buying Today.

In that paper, Stern described a phenomenon he called Suggestion Impulse Buying, which “is triggered when a shopper sees a product for the first time and visualizes a need for it.”

Suggestion Impulse Buying says that customers buy things not necessarily because they want them, but because of how they are presented to them. This simple idea—that where products are placed can influence what customers will buy—has fascinated retailers and grocery stores ever since the moment Stern put the concept into words.

How to Sell Candy Bars

Candy sales are very seasonal. Bulk candy purchases tend to be made around Halloween and other holidays, which means that during the majority of the year candy never makes it onto the grocery list. Obviously, this isn’t what candy companies want, since they would prefer to have sales continue throughout the year.

Because candy isn’t an item you are going to seek out during most trips to the grocery store, it is positioned in a highly visible place where you’ll see it even if you aren’t looking for it: the checkout line.

But why the checkout line? If it was just about visibility, the store could put candy right by the front door so that everyone saw it as soon as they walked inside.

The second reason candy is at the checkout line is because of a concept called decision fatigue. The basic idea is that your willpower is like a muscle. Like any muscle, it gets fatigued with use. The more decisions you ask your brain to make, the more fatigued your willpower becomes.

If you saw a box of candy bars at the front door, you would be more likely to resist grabbing one. By the time you get to the checkout counter, however, the number of choices about what to buy and what not to buy has drained your willpower enough that you give in and make the impulse purchase. This is why grocery stores place candy at the checkout counter and not the front door.

OK, but what does a Kit Kat bar have to do with building better habits?

3 Ways to Change Your Habits

At a basic level, a store that wants to sell more candy wants to change human behavior. And whether you’re trying to lose weight, become more productive, create art on a more consistent basis, or otherwise build a new habit, you want to change human behavior too. Let’s take a look at what the grocery store did to drive additional purchases of candy bars and talk about how those concepts apply to your life.

First, grocery stores removed the friction that prevented a certain behavior. They realized that people were only buying candy in bulk around the holidays, so they cut down the size of the purchase and sold candy bars one at a time.

You can do the same thing with your habits. What are the points of friction that prevent you from taking a behavior right now? Does the task seem overwhelming (like the equivalent of buying 40 pieces of candy when you only want 1 piece)? Then start with a small habit. Examples include: doing 10 pushups per day rather than 50 per day, writing 1 post per week rather than 1 per day, running for 5 minutes rather than 5 miles, and so on. Starting small is valuable because objects in motion tend to stay in motion.

Second, grocery stores created an environment that promoted the new behavior. Retailers recognized that unless the holidays were around the corner, people were unlikely to browse the store and seek out candy bars, so they moved the candy bars to a place where people didn’t have to seek them out: the checkout line.

How can you change your environment so that you don’t have to seek out your new habits? How can you adjust your kitchen so that you can eat healthy without thinking? How can you shift your workspace so that digital distractions are minimized? How can you create a space that promotes the good behaviors and prevents the bad ones? Surround yourself with better choices and you’ll make better choices.

Third, grocery stores stacked the new behavior at a time when the energy was right for it. As we’ve already covered, you’re more likely to give in and buy the candy bar at the checkout line because decision fatigue has set in. Of course, it’s not just decision fatigue that saps our willpower and motivation. There are a variety of positive and negative daily tasks that drain your brain. Periods of intense focus, frustration, self-control, and confusion are all examples of how you can deplete your mental battery.

When it comes to building better habits, you can deal with this issue in two ways.

- You can take active steps to reduce the areas that deplete your willpower. In the words of Kathy Sierra, you have to “manage your cognitive leaks.” This means eliminating distractions and focusing on the essential. It’s much easier to stick with good habits if you subtract the negative influences. Self-control has a cost. Every time you use it, you pay. Make sure you’re paying for the things that matter to you, not the stuff that is useless or provides marginal value to your life.

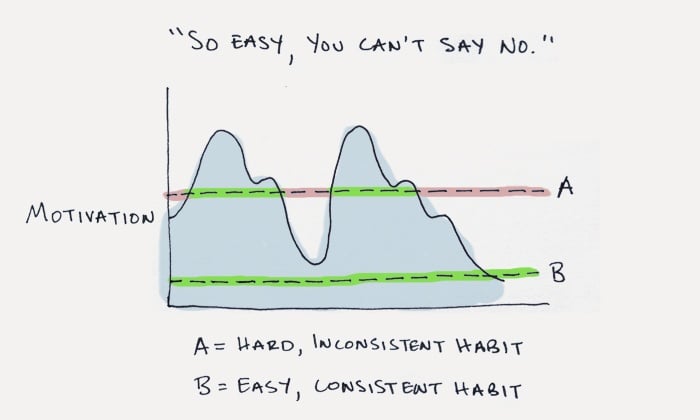

- You can perform your habit at a time when your energy is right for it. Stores ask you to buy candy bars when you are most likely to say yes. Similarly, you should ask yourself to perform new habits when you are mostly likely to succeed. Your motivation ebbs and flows throughout the day, so make sure the difficulty of your habit matches your current level of motivation. Big habits are usually best if attempted early in the day when your motivation and willpower are high (or after a lunch break when you’ve had a chance to eat and rejuvenate).

Your Environment Drives Your Habits

We like to think that we are in control of our behavior. If we buy a candy bar, we assume it is because we wanted a candy bar. The truth, however, is that many of the actions we take each day are simply a response to the environment we find ourselves in. We buy candy bars because the store is designed to get us to buy candy bars.

Similarly, we stick to good habits (or repeat bad habits) because the environments that we live in each day—our kitchens and bedrooms, our offices and workspaces—are designed to promote these behaviors. Change your environment and your behavior will follow.

This article was originally published on JamesClear.com.