In 1985, Coca-Cola made the decision to switch their formula, creating essentially a different-tasting soda product. They called it New Coke. The sweeter version was arrived at after 190,000 nationwide taste tests that cost roughly $4 million. The result was not positive. Coca-Cola drinkers didn’t like the new taste — 39% or so were extremely loyal to the original — and Pepsi, their biggest rival, was able to say “The other guy blinked.” (That means Coke had reformulated to taste more like Pepsi.) The entire experiment lasted all of 79 days before Coke switched back to the original formula, which it now was calling Coke Classic.

Coca-Cola is a very successful company, but in this specific case, they failed badly. Why?

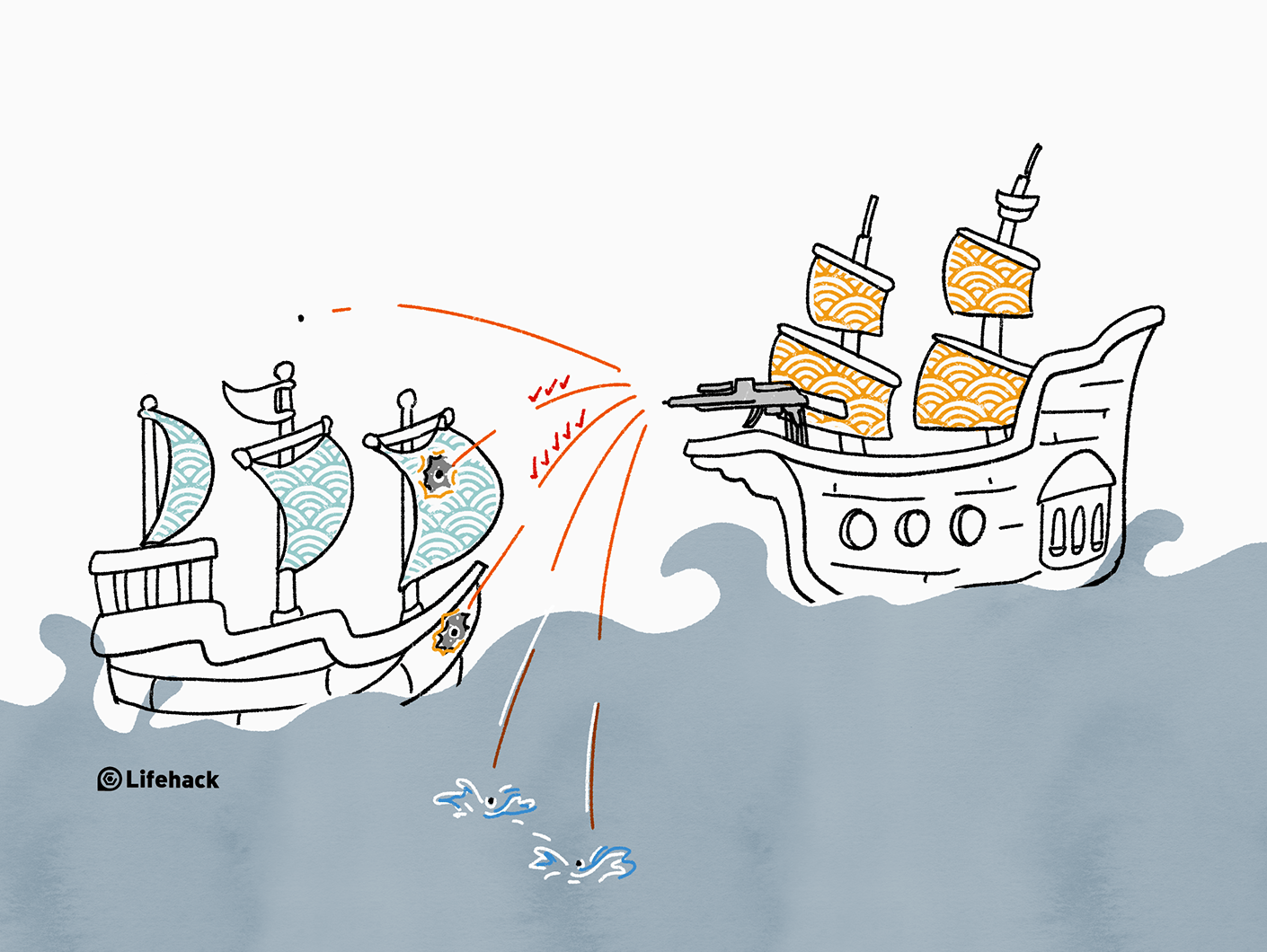

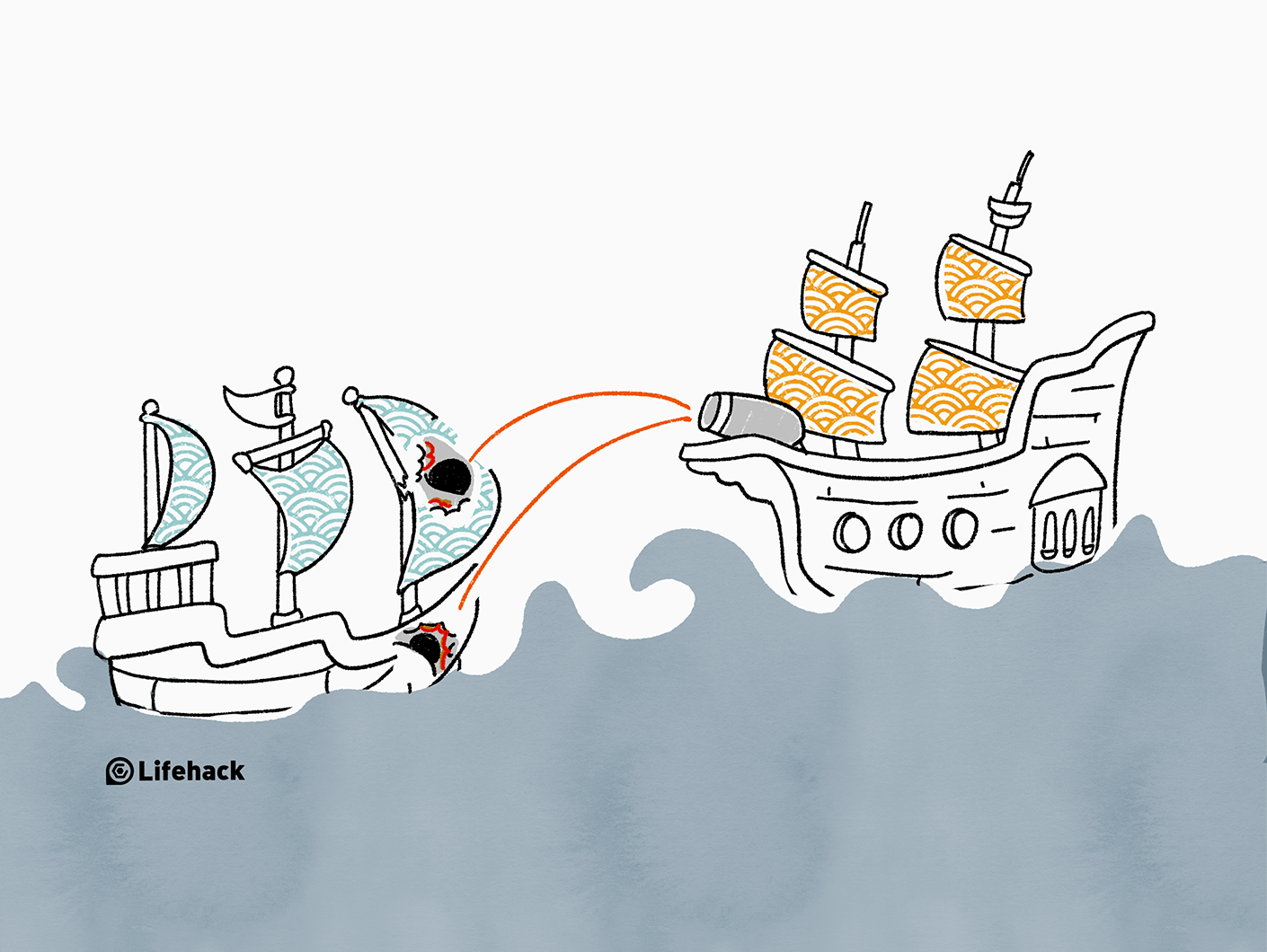

Fire bullets, then cannonballs

Coca-cola was confident about their new product so they invested a lot in it and threw this “cannonball” to the market. When customers didn’t like this new product, it means the cannonball missed the target. This brought Coca-cola a great loss at the end.

If Coca-Cola tested their product carefully, launched the new product in only selective places, like shooting out bullets, they might not fail tremendously like that.

This idea of “fire bullets, then cannonballs” was developed by Jim Collins in his book Great by Choice.

The basic principle is this: during trying times, oftentimes people look for big solutions and giant leaps. They want to show dramatic success to emerge from the failure. But that’s actually the wrong approach.

Successful people take small steps before making big leaps.

This isn’t just work. Think about dating, for example, you don’t often just go approach someone and ask to be super serious or get engaged. You try to start to talk to them first, then go on a few dates, and include them when you hang out with friends.

Or think about when you’re buying a car. Very few people walk into a car dealership with no research done and spend $35,000. They visit several. They talk to friends. They do research.

In this model, bullets are small steps to test the idea first. Cannonballs are giant leaps to make a great impact.

You deal with bullets first, taking small steps to test an idea first e.g. prototype, test, redesign, and test again; when you’ve got enough experience to know this idea works or is welcome by customers, shoot.

The cannonballs stage is about scaling the idea up, publicly launching it in a wide scale, and making it loud.

By carefully testing something before you try to make it big, you can prevent big idea failure.

How to fire bullets

A bullet is a small empirical test that should meet these criteria:

- low cost

- low risk, meaning minimum consequence

- low distraction, meaning not having great impact on the overall

A bullet might be a piece of research you find, or a small focus group. They come in different forms.

Once you’ve fired bullets and see some results, you enter into this process:

- Assess: Did your bullets hit anything? What can you learn from the failed bullets to improve other bullets?

- Consider: Can any of the successful bullets worth turning into a cannonball? Do you need to fire another bullet to make sure it?

- Convert: When confirmed the success of bullets, concentrate resources and fire a cannonball

- Terminate: The bullets that show no evidence of eventual success.

The process of reviewing the bullets is more important than the bullets themselves. Let’s say a student gets an “A” on a test, but he cheated. The “A” might be seen as the cannonball-esque result, but the process is highly flawed and could encourage more negative behavior. Reviewing your process is crucial.

Now let’s think of all this in terms of the New Coke marketing blunder. Before those 190,000 nationwide taste tests at a cost of $4 million, and before they launched their New Coke, they could have try out bullets e.g. market New Coke as freebies in small size and distributed to only a few shops, use different ways to test out its popularity in different regions first; before they muster all the effort to a big launch of it and had to return to use the original formula of Coke.

Bullets first, and only then should you fire the big launch cannonball.

How can you do this in your life?

Think of it along these lines:

Step 1: Find your bullets

- What small things can you do to test out your ideas?

- Are they at low cost, low risk and low distraction?

- Are there any existing ways that you can take reference of/learn from?

Step 2: Fire your bullets and review them

- Hit any target? if not, why?

- What can you learn from the failed bullets?

- For the successful bullets that hit the target, when is it time to use cannonball to hit the target?

Again, this is about more than ideas at work. If you’re courting a relationship, bullets might involve learning about the person from their friends, setting up coffee, and sending small trinkets. The “cannonball” would be the relationship itself, but you can’t jump immediately to that. There needs to be some bullets fired first — and some might miss.

You can learn more in Great by Choice, which argues that while we can’t predict the future, we can shape it through dedicated actions such as bullets before cannonballs.